Un universo de enlaces exquisitos: Lizard III Tunga (1977-1997).

- OCA | News

- 10 oct 2020

- 27 Min. de lectura

Actualizado: 15 oct 2020

Durante estos quince años, Tunga ha sido ante todo escultor (constructor de los objetos incluidos en esta muestra), creador de performances e inventor de ficción.

REINALDO LADDAGA / ArtNexus / Octubre 10, 2020 / Fuente externa

En septiembre, se inauguró la primera exposición integral de la obra de Tunga comisariada por Carlos Basualdo, en el Centro de Estudios Curatoriales del Bard College, ubicado a pocas horas al norte de la ciudad de Nueva York. Tunga, quien vive y trabaja en Río de Janeiro, es el miembro más joven de la gran generación de artistas brasileños (Cildo Meireles, Jose Resende y Waltercio Caldas son algunos de los otros) que siguieron las figuras de Helio Oiticia y Lygia Clark.

Es la sombra de este último (junto con los de Robert Morris y, más tenuemente, de Joseph Beuys) la que tiñe la mayoría de estas piezas de fieltro, caucho y cuero de finales de los setenta, las primeras obras importantes de Tunga y las que abre el espectáculo en Bard College. Por muy llamativas que sean algunas de estas piezas, e incluso cuando contienen elementos que anticipan su obra posterior, se percibe una ruptura bastante ordenada en la obra de Tunga hacia principios de los ochenta: es básicamente a partir de este momento cuando se despliega la singularidad de su obra. . El período de quince años que sigue desde ese momento hasta mediados de la década actual constituye el núcleo de esta exposición. Durante estos años, Tunga es sobre todo escultor (constructor de los objetos incluidos en esta exposición), creador de performances e inventor de ficciones (generalmente ha publicado su obra en forma de panfleto que complementa en ocasiones algunas de sus esculturas). .1

Es un triunfo por parte del artista y del comisario que sea tan difícil imaginar cualquiera de los objetos expuestos en la muestra, una vez que uno los ha visto juntos, separados unos de otros como los imaginaría ensamblados en cualquier otra moda. Por lo tanto, a continuación, se describirán precisamente como aparecieron en este sitio y en esta ocasión específica. Las obras ensambladas de 1981-1994 se distribuyen en anillo en seis salas. En la primera habitación a la altura de los tobillos, se trata de un bucle de película en constante movimiento y un proyector. Esta es una obra de 1981, año. La imagen registrada en la película que circula por la habitación semi-oscura se proyecta en una pared. Es una película de un túnel en Río de Janeiro, filmada desde un automóvil. El túnel está desierto, la atmósfera es nocturna. La imagen avanza a cámara lenta en un blanco y negro ligeramente quemado. Dado que los dos extremos de la película se han pegado juntos, es como si uno nunca lograra atravesar el túnel. Se escucha música: una vieja balada, Night and Day. Una voz, acompañada de una gran orquesta, comienza a cantar en inglés la letra estándar de la balada: "Noche y día / día y noche". Pero como en algunas de las obras de Bruce Nauman de la época de Ão (Live and Let Die de 1983, por ejemplo) la situación discursiva se complica cada vez más –o más bien se deteriora– y la voz acaba cantando sin sentido, "Day and day / noche y noche "como si no pudiera evitar perder coherencia. Como la imagen de la película, la banda sonora se repite ad infinitum. La impresión es la de una degradación suspendida, un poco como ciertas novelas de Maurice Blanchot (La sentencia de muerte o Aminadab) o incluso algunos cuentos del narrador cuyo nombre Tunga menciona frecuentemente cuando habla de su educación e influencias: Edgar Allan Poe.La instalación es, al principio, banalmente agradable y luego inmediatamente se vuelve enervante. La sala en la que se encuentra es a la vez parte cine, parte salón de baile y parte cámara de tortura. El vínculo entre lo banal (incluso lo idiota a veces) y lo aterrador es constante en la obra de Tunga tal como lo es, de manera diferente en la obra del artista estadounidense Mike Kelley, su contemporáneo. El vínculo reaparece en la gigantesca escultura de la sala que se abre a la izquierda de la sala Ão –que es donde probablemente iría el espectador mientras continúa su recorrido por la exposición (recorrido en el que, cabe mencionar, uno nunca escapa la música, la voz diversamente empalmada, el acompañamiento orquestal, las palabras "noche y día").

Palindromo incesto (Palindrome Incesto), de 1990, no es fácil de describir ni fácil de mirar. Tres enormes dedales metálicos, uno de ellos con su superficie de hierro expuesta, otro cubierto por delgadas láminas de cobre, el tercero con limaduras, todos con trozos de imanes adheridos a sus superficies aquí y allá, yacen de costado por todo el espacio, conectados por puñados. de alambre de cobre del que cuelgan agujas de coser igualmente enormes, curvas y rectas. Tres termómetros de vidrio llenos de mercurio completan el conglomerado. En esta obra se incluye todo el repertorio de materiales que suele emplear Tunga: imanes, hierro, cobre, vidrio. Los tríos, las tríadas trenzadas que se repiten obsesivamente en sus piezas también están aquí. Pero hay algo en Palindrome Incest que es particularmente desconcertante. El universo referencial de esta obra es convencionalmente femenino: es el universo de una determinada feminidad. Es la feminidad del tocador o del cuarto de costura, la feminidad de la languidez, del placer lento y lánguido. (Es significativo que uno de los primeros grupos de esculturas verdaderamente importantes de Tunga se titula Les Bijoux de Mme. De Sade (Joyas de la mina de Sade). Pero aunque ese universo se ha conservado, también se ha perturbado curiosamente. algo absolutamente brutal en la obra y algo absolutamente doloroso. Como se aprecia en ciertos cuadros de Balthus, una violencia absoluta se muestra en el espacio de placeres domésticos tranquilos que la cultura ha reservado para las mujeres. (El tema de "una mujer violada" es presente de manera más o menos constante en las obras de Tunga).

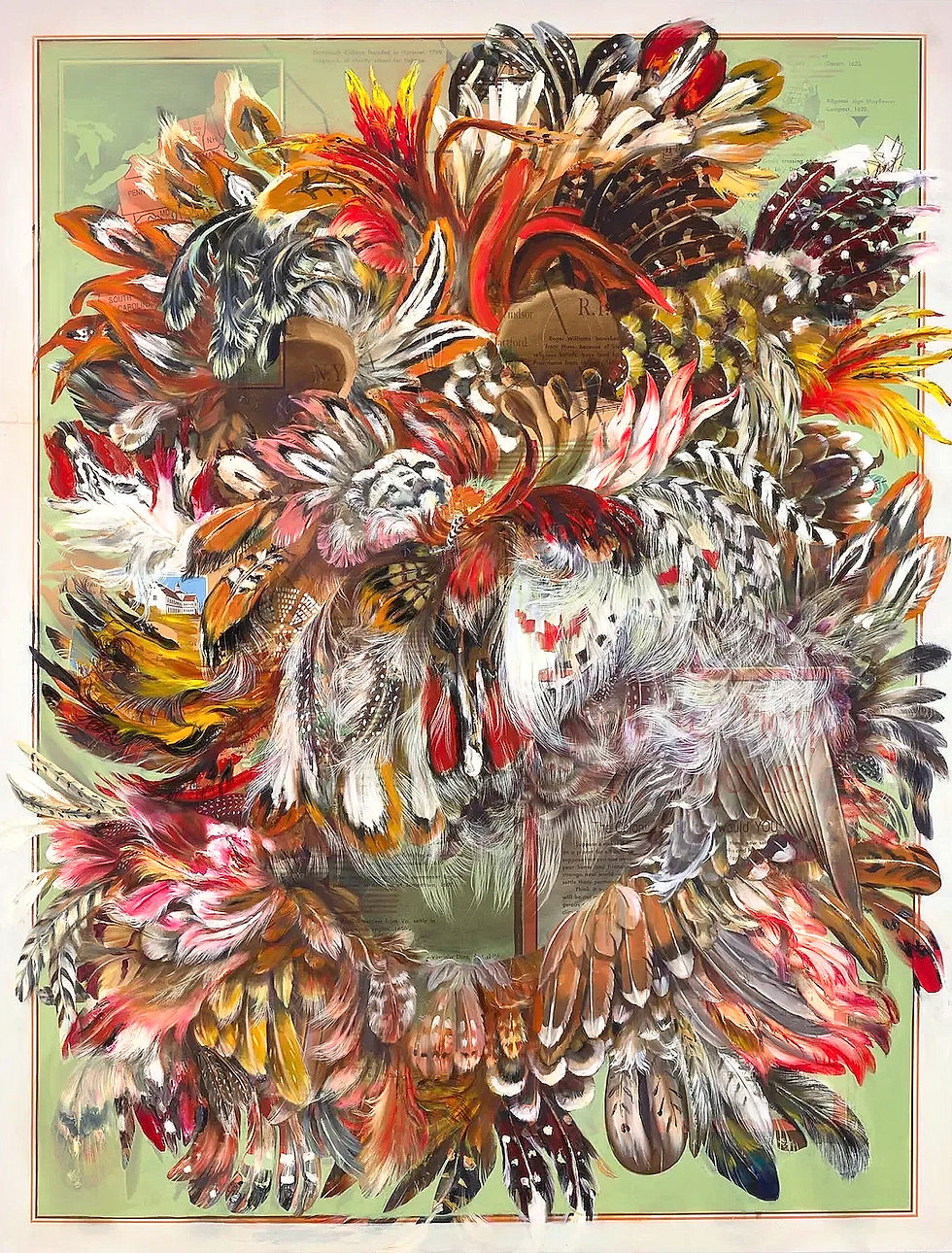

La fuerza de la pieza está ligada en parte al contacto –que, al verlo, es difícil no establecer– entre la escena de referencia, el mundo tenue del cuarto de costura o el tocador, y la presencia masiva de esas formas metálicas. Lo mismo ocurre en la siguiente sala, que está íntegramente ocupada por una pieza de 1989 titulada Lagarte III (Lagartos III). Aquí lo que encontramos son dos conjuntos rectangulares en pie formados por planchas de ropa y tipos de peines a los que se adhieren, mediante pequeños bloques de imanes amontonados, gruesos haces de alambre de cobre que aluden a mechones de cabello. Sobre los cabellos cobrizos se disponen, aquí y allá, varias estatuas diminutas de seres hechos de mitades de lagarto unidas. Hay cerebros diminutos en los hierros. Los mechones de cabello se entrelazan en dos esquinas de la habitación con dos garrotes cubiertos también de imanes. El objeto presenta un desafío para cualquiera que lo describa e interprete en términos de significado profundo. De nada sirve intentar descifrar esta obra –o cualquier obra de Tunga– como si se tratara de una cuestión de alegoría. Lo único que aparentemente se puede discernir sobre lo que el artista deseaba hacer es que quería poner en contacto ciertas cosas: cabellos e imanes de alambre de cobre, cerebros y lagartijas quiméricas, peines y garrotes hipertrofiados. ¿Es esto una especie de objeto surrealista? La respuesta a esta pregunta no es sencilla. El surrealismo fue parte central de la educación de Tunga, pero menos pintura que ciertas obras literarias surrealistas, menos Miro o Matta que bretón, y menos incluso bretón que varios artistas que renunciaron al movimiento como Antonin Artaud o Georges Bataille, por no hablar de algunos que pertenecen al canon del surrealismo como Raymond Roussel, por ejemplo, o el mismo Poe. Y sin embargo, si la composición de los objetos del surrealismo se dispuso para producir lo que Walter Benjamin llamó una iluminación profana, una luminosidad, no hay nada menos surrealista que Lizards, que produce un chillido más que una chispa, un disgusto más que un brillo. Se trata de una pieza en la que los componentes entran en contacto entre sí menos como hacer un paraguas y una máquina de coser sobre una mesa de disección (según la imagen de Lautréamont que Breton citaría como ejemplificación de la imagen surrealista) como entra una uña. contacto con la superficie de una pizarra.

Paul Valéry, en un texto de 1932 sobre Corot, dice que hay dos grandes tipos de artistas. Por un lado, están los artistas cuyo objetivo es, citando a Valéry, hacernos "compañeros en su mirada feliz en un día hermoso". Corot ejemplificaría precisamente a este grupo. Y por otro lado, están los Delacroix, los Wagner, los Baudelaire, cuyo objetivo es "procurar de sus entornos la acción más enérgica sobre los sentidos", preocuparse por el "dominio del alma a través del canal de los sentidos, "ansiosos" de alcanzar y como poseer –en el sentido diabólico del término– ese punto débil y escondido del ser que lo expone y lo gobierna enteramente por el desvío de sus entrañas y profundidades orgánicas ”2 Tunga. (como Nauman, como Richard Serra) pertenecen claramente a esta última categoría. En las grandes instalaciones es evidente el deseo del artista de impactar en el espectador y controlar sus reacciones. Hay algo de hipnotizador (magnetista como solían decir hace algún tiempo) en el artista que compuso esas obras. Ese deseo es menos visible, sin embargo, en sus obras menores que se distribuyen en dos salas idénticas en la parte trasera del edificio –en la parte del edificio que da a la sala donde Ão se extiende– unidas por un pasillo algo estrecho. Una parte de estas piezas son versiones separadas, en general, realizadas anteriormente, como si fueran bocetos, de objetos que forman parte de la composición de las instalaciones: garrotes, anillos, trenzas, peines, haces de alambre de cobre. Todo en estas habitaciones se asemeja a un órgano humano y al mismo tiempo a una joya. La combinación de crueldad y lujo que parece imponerse a estas dos estancias dota de una extraña luz a las obras del pasillo que las separa.

De hecho, en el pasillo entre las dos salas se encuentran las obras más, digamos, líricas de la exposición. Se trata de una serie de esculturas, realizadas durante los últimos diez años, desde 1986, denominadas Eixos Exoginos (Hachas Exógenas). Cualquiera recordaría seguramente esas urnas de uso común en los libros de psicología sobre la visión en cuyo contorno se podía distinguir el perfil de un rostro humano. El mismo principio opera en estos trabajos. Son columnas torneadas de tal manera que en sus bordes se puede percibir, en cada caso, en negativo o en su ausencia, el perfil del cuerpo completo y desnudo de una mujer, diferente cada vez. Hay cinco de estas obras en la exhibición y como grupo hacen pensar en una danza elemental y congelada. Están relacionadas, por supuesto, con las impresiones de mujeres realizadas en papel o tela producidas en los años cincuenta y sesenta por Robert Rauschenberg e Yves Klein. Pero su apariencia recuerda más de cerca ciertas obras del escultor que, en conversación Tunga, curiosamente parece mencionar con mayor frecuencia: Constantin Brancusi.

El día de la inauguración del espectáculo, este grupo de columnas o retratos resonó con otros dos grupos móviles de mujeres: las participantes en dos representaciones. En un Xipofagas capilares (Capillary Xipophagi) de 1985) dos niñas fueron trenzadas juntas por el cabello como si padecieran una forma relativamente benigna (para ellas) de ser gemelas siameses, y simplemente caminaban de un lado a otro. En la otra actuación, Sero te Amavi (Te amé tardíamente) de 1992, tres mujeres adolescentes en camisa, con dedales, agujas y anillos en la mano, asumieron, congeladas, una serie de poses. En cada una de las poses, cada una de las mujeres, a todas las apariencias indiferentes a las demás, se apoyaba en las otras dos. (Siempre había algo insuficientemente erguido en las figuras, en las construcciones que formaban). ¿Qué idea regulaba la composición de las poses de estas tres mujeres? Existe una figura topológica llamada nudo borromeo que los lectores de las últimas obras de Lacan deben conocer muy bien. Un nudo borromeo se compone de tres anillos entrelazados de modo que si uno de los tres se rompe, los otros dos también se liberarán. Lo mismo ocurre con una trenza de tres hebras: si se corta alguna de ellas las otras dos se dispersarán. Estos tres adolescentes actuaban como un nudo borromeo o una trenza de tres hilos: bastaba que uno de ellos cayera para que los otros dos también lo hicieran. De tal manera que, en todo momento del transcurso de la actuación del grupo, cada adolescente se contactaba con los demás y se apegaba a los demás en la medida de lo posible.

¿Cuál es el origen de estos seres? La inspiración de esta obra (y la redacción de su título) proviene de un pasaje de las Confesiones de San Agustín. El modelo de este grupo, este conglomerado o esta trenza es la Santísima Trinidad de la doctrina cristiana. Pero, ¿qué podría encontrar especialmente atractivo este artista, tan pequeño cristiano en todas las apariencias, en esa figura tradicional? ¿Qué hay para Tunga que sea particularmente fascinante en la Santísima Trinidad?

La primera vez que vi esta actuación, en Nueva York, hace solo unos años, las tres mujeres adolescentes estaban en el otro extremo de una larga galería. En la parte delantera de la galería había una caja de acrílico llena de papel por la que se deslizaban tres serpientes. ¿Cuál es la relación, me preguntaba en ese momento, entre un grupo de serpientes y tres adolescentes inmóviles que representan (la palabra probablemente sea inadecuada) a la Santísima Trinidad? Ningún ser aparece más en la obra de Tunga que las serpientes, en particular, las serpientes entrelazadas. Una de sus apariciones tiene ahora una década. En 1987, Tunga produjo las esculturas y los conceptos para una película dirigida por Arthur Omar con el título Nervo de prata (Nervios de plata). En una secuencia de la película, la cámara enfoca con evidente deleite a varias serpientes que se entrelazan. La cámara captura el roce de piel contra piel. Es como si las serpientes fueran movidas por el deseo de hacer contacto entre sí de la manera más completa posible, incluso al precio de perder su propia distinción en una pila o masa de partes indistinguibles. Por extraña que parezca la idea, es posible que Tunga encuentre fascinante la figura de la Santísima Trinidad en la medida en que le recuerde el fascinante espectáculo de las serpientes entrelazadas. ¿No es la Santísima Trinidad tradicionalmente una combinación de tres seres que hacen contacto extático y total entre sí? ¿En qué se combinan la máxima absorción por parte de cada uno, abandonados al placer de convertirse en experiencia y la máxima comunicación con las otras partes, igualmente abandonadas? La lectura es violenta y, sin embargo, creo, adecuada. Una idea de la Santísima Trinidad, el trío de adolescentes, las serpientes trenzadas. Las trenzas de metal que aparecen brevemente a lo largo de esta pieza son quizás apariciones momentáneas de una fantasía de total placer en la perfecta absorción y pura comunicación con los demás.

El día de la inauguración del espectáculo, este grupo de columnas o retratos resonó con otros dos grupos móviles de mujeres: las participantes en dos representaciones. En un Xipofagas capilares (Capillary Xipophagi) de 1985) dos niñas fueron trenzadas juntas por el cabello como si padecieran una forma relativamente benigna (para ellas) de ser gemelas siameses, y simplemente caminaban de un lado a otro. En la otra actuación, Sero te Amavi (Te amé tardíamente) de 1992, tres mujeres adolescentes en camisa, con dedales, agujas y anillos en la mano, asumieron, congeladas, una serie de poses. En cada una de las poses, cada una de las mujeres, a todas las apariencias indiferentes a las demás, se apoyaba en las otras dos. (Siempre había algo insuficientemente erguido en las figuras, en las construcciones que formaban). ¿Qué idea regulaba la composición de las poses de estas tres mujeres? Existe una figura topológica llamada nudo borromeo que los lectores de las últimas obras de Lacan deben conocer muy bien. Un nudo borromeo se compone de tres anillos entrelazados de modo que si uno de los tres se rompe, los otros dos también se liberarán. Lo mismo ocurre con una trenza de tres hebras: si se corta alguna de ellas las otras dos se dispersarán. Estos tres adolescentes actuaban como un nudo borromeo o una trenza de tres hilos: bastaba que uno de ellos cayera para que los otros dos también lo hicieran. De tal manera que, en todo momento del transcurso de la actuación del grupo, cada adolescente se contactaba con los demás y se apegaba a los demás en la medida de lo posible.

¿Cuál es el origen de estos seres? La inspiración de esta obra (y la redacción de su título) proviene de un pasaje de las Confesiones de San Agustín. El modelo de este grupo, este conglomerado o esta trenza es la Santísima Trinidad de la doctrina cristiana. Pero, ¿qué podría encontrar especialmente atractivo este artista, tan pequeño cristiano en todas las apariencias, en esa figura tradicional? ¿Qué hay para Tunga que sea particularmente fascinante en la Santísima Trinidad?

La primera vez que vi esta actuación, en Nueva York, hace solo unos años, las tres mujeres adolescentes estaban en el otro extremo de una larga galería. En la parte delantera de la galería había una caja de acrílico llena de papel por la que se deslizaban tres serpientes. ¿Cuál es la relación, me preguntaba en ese momento, entre un grupo de serpientes y tres adolescentes inmóviles que representan (la palabra probablemente sea inadecuada) a la Santísima Trinidad? Ningún ser aparece más en la obra de Tunga que las serpientes, en particular, las serpientes entrelazadas. Una de sus apariciones tiene ahora una década. En 1987, Tunga produjo las esculturas y los conceptos para una película dirigida por Arthur Omar con el título Nervo de prata (Nervios de plata). En una secuencia de la película, la cámara enfoca con evidente deleite a varias serpientes que se entrelazan. La cámara captura el roce de piel contra piel. Es como si las serpientes fueran movidas por el deseo de hacer contacto entre sí de la manera más completa posible, incluso al precio de perder su propia distinción en una pila o masa de partes indistinguibles. Por extraña que parezca la idea, es posible que Tunga encuentre fascinante la figura de la Santísima Trinidad en la medida en que le recuerde el fascinante espectáculo de las serpientes entrelazadas. ¿No es la Santísima Trinidad tradicionalmente una combinación de tres seres que hacen contacto extático y total entre sí? ¿En qué se combinan la máxima absorción por parte de cada uno, abandonados al placer de convertirse en experiencia y la máxima comunicación con las otras partes, igualmente abandonadas? La lectura es violenta y, sin embargo, creo, adecuada. Una idea de la Santísima Trinidad, el trío de adolescentes, las serpientes trenzadas. Las trenzas de metal que aparecen brevemente a lo largo de esta pieza son quizás apariciones momentáneas de una fantasía de total placer en la perfecta absorción y pura comunicación con los demás.

Pero Tunga también encontraría inmediatamente atractivo que, bajo el título de Agua sexual (el título del poema del que se tomaron los versos citados), Neruda evoca un estado catastrófico del cuerpo. Una figura recurrente en las representaciones recientes del artista (representaciones que no se han incluido en la exposición de Bard) es un hombre que lleva una maleta. La maleta se abre de repente y de ella cae un montón de miembros seleccionados mezclados con cubos de gelatina. ¿Estas extremidades pertenecen a los adolescentes desaparecidos en Belatedly I Loved You? No estamos en condiciones de responder a esa pregunta. Pero es interesante que el show de Bard cerrara con una imagen que indica, más allá de sí misma, algún oscuro desastre. No es imposible que, a estas alturas del visionado, quien ha pasado por la exposición pueda percibir que esa voz que en Ão sigue cayendo en un balbuceo deslumbrante, o la escena de un cuarto de costura invadido por metales, o las lagartijas siameses. y diminutos cerebros mezclados con cabellos que se extienden sin límite, o unas campanillas lanzadas como dados e impregnadas de un líquido lechoso, o el colapso sonámbulo de un nudo de adolescentes, que todas esas figuras remiten a una existencia amenazada. (En un video que se muestra a Bard en una habitación lateral, Tunga está construyendo varias piezas. Sus gestos son extraños, es como si, al mismo tiempo que hace sus construcciones, Tunga quisiera mantenerlas a distancia para evitar que sabe qué peligro.) Un afecto específico es capaz, creo, de producir este espectáculo: un placer, una euforia, en total contacto, enteramente entrelazado, en cada uno de sus momentos, con un malestar. La naturaleza específica de este afecto es, para este escritor, nueva.

NOTAS

1. Una lista completa de estas actividades se puede encontrar ahora en un libro del artista publicado este año: Barroco de lirios, (São Paulo: Kosac & Naify, 1997). La bibliografía sobre Tunga es aún limitada. En el catálogo de la exposición se publicarán bellos textos escritos por Guy Brett, Suely Rolnik y Carlos Basualdo.

2. Paul Valéry, Pieces sur I'art (París: N.R.F., 1936) 137-138.

3. Edgar Allan Poe, trad. D. Rolfe y J. Gómez de la Sema (Madrid: Ccitedra, 1991) 169.

4. Pablo Neruda, Residencia en la tierra (Madrid: Ccitedra, 1986).

REINALDO LADDAGA

Autor y Ph.D. Candidato de la Universidad de Nueva York. Es profesor en varias universidades de Argentina y Estados Unidos. Ha publicado extensamente sobre temas de estética, arte y literatura.

Encuesta Tunga A (1977-1997). Un universo de enlaces exquisitos

During these fifteen years, Tunga has been first and foremost a sculptor (builder of the objects included in this exhibit), a creator of performances, and an inventor of fiction.

REINALDO LADDAGA

In September, the first comprehensive exhibit of the work of Tunga curated by Carlos Basualdo, opened at the Center for Curatorial Studies at Bard College, located a few hours north of New York City. Tunga, who lives and works in Rio de Janeiro, is the youngest member of the great generation of Brazilian artists (Cildo Meireles, Jose Resende, and Waltercio Caldas are a few of the others) who followed the figures of Helio Oiticia and Lygia Clark.

It is the shadow of the latter (along with those of Robert Morris and, more tenuously, Joseph Beuys) that colors the majority of these pieces of felt, rubber, and leather of the end of the seventies –Tunga's first important works and those that open the show at Bard College. Remarkable as some of these pieces are– and even when they contain elements that anticipate his later work –a fairly neat break is visible in Tunga's work toward the beginning of the eighties: it is basically from this moment on that the uniqueness of his work unfolds. The fifteen-year period that follows from that moment through the middle of the current decade constitutes the core of this exhibit. During these years, Tunga is above all a sculptor (builder of the objects included in this exhibit,) a creator of performances, and an inventor of fictions (he has generally published his work in pamphlet form which complements at times some of his sculptures).1

It is a triumph on the part of the artist and the curator that it would be as difficult to imagine any one of the objects displayed in the exhibit, once one has seen them together, separated from one another as it would imagine them assembled in any other fashion. Thus, in what follows, they will be described precisely as they appeared at this site and on this specific occasion. The assembled works from 1981-1994 are spread out in a ring in six rooms. In the first room at ankle height, this is a film loop in constant motion and a projector. This is a work from 1981, Ão. The image registered on the film that circulates through the semi-dark room is projected on a wall. It is a film by a tunnel in Rio de Janeiro, shot from a car. The tunnel is deserted, the atmosphere nocturnal. The image advances in slow motion in a slightly burnt black and white. Since the two ends of the film have been glued together, it is as if one never manages to traverse the tunnel. Music can be heard: an old ballad, Night and Day. A voice, accompanied by a large orchestra, begins to sing in English the standard lyrics of the ballad: "Night and day/day and night." But as in some of the works of Bruce Nauman from the period of Ão (Live and Let Die from 1983, for example) the discursive situation grows increasingly complicated –or rather, deteriorates– and the voice ends up singing nonsensically, "Day and day/night and night" as if it were unable to keep from losing coherence. Like the film image, the soundtrack repeats ad infinitum. One's impression is that of a suspended degradation, a bit like certain novels of Maurice Blanchot (The Death Sentence or Aminadab) or even some tales by the narrator whose name Tunga mentions frequently when speaking of his education and influences: Edgar Allan Poe.

The installation is, at first, banally pleasant, and then immediately becomes enervating. The room in which it is housed is at once a part cinema, part dance hall, and part torture chamber. The link between the banal (even the idiotic at times) and the frightening is constant in Tunga's work as it is, in a different fashion in the work of the American artist Mike Kelley, his contemporary. The link reappears in the gigantic sculpture in the room that opens to the left of the Ão room –which is where the viewer would probably go as he continues his tour of the exhibit (a tour in which, it should be mentioned, one never escapes the music, the variously spliced voice, the orchestral accompaniment, the words "night and day.")

Palindromo incesto (Palindrome Incest), from 1990, is not easy to describe –nor easy to look at. Three enormous metal thimbles, one of them with its iron surface exposed, another covered by thin copper sheets, the third with filings, all with chunks of magnets attached to their surfaces here and there, lie on their sides throughout the space, connected by handfuls of copper wire on which hang equally enormous, curved and straight sewing needles. Three glass thermometers filled with mercury complete the conglomeration. The entire repertory of materials that Tunga usually employs are included in this work: magnets, iron, copper, glass. The trios, the braided triads that recur obsessively in his pieces are here as well. But there is something in Palindrome Incest that is particularly disconcerting. The referential universe of this work is conventionally feminine: it is the universe of a specific femininity. It is boudoir or sewing-room femininity, femininity of languor, of slow and languid pleasure. (It is significant that one of the first groups of truly important sculptures by Tunga is titled Les Bijoux de Mme. de Sade (Mine. de Sade's jewels). But while that universe has been preserved it has also been curiously disturbed. For there is something absolutely brutal in the work and something absolutely painful. As seen in certain paintings by Balthus, an absolute violence is shown in the space of tranquil, domestic delights which culture has set aside for women. (The theme of "a woman violated" is present in a more or less constant fashion in Tunga's works.)

The power of the piece is linked in part to the contact –which, when seeing it is difficult not to establish– between the scene of reference, the faint world of the sewing room or the boudoir, and the massive presence of those metal forms. The very same thing occurs in the following room, which is wholly occupied by a piece from 1989 titled Lagarte III (Lizards III). Here what we find are two standing rectangular assemblages formed of clothes irons and types of combs to which are adhered, by means of small, piled-up blocks of magnets, thick bundles of copper wire that allude to strands of hair. On the copper hair are arranged, here and there, several tiny statues of beings made of lizard halves joined together. There are tiny brains on the irons. The strands of hair weave together in two corners of the room with two garrotes covered as well in magnets. The object presents a challenge to anyone describing it as well as interpreting it in terms of profound meaning. It is useless to attempt to decipher this work –or any work of Tunga's– as if it were a matter of allegory. The only thing that can apparently be discerned about what the artist wished to do is that he wanted to place certain things in contact with one another: copper wire-like hair and magnets, brains and chimeric lizards hypertrophied combs and garrotes. Is it this a sort of surrealist object? The answer to this question is not simple. Surrealism was a central part of Tunga's education, but less it's painting than certain surrealist works of literature, less Miro or Matta than Breton, and less even Breton than several artists who renounced the movement like Antonin Artaud or Georges Bataille, not to mention some who belong to the canon of Surrealism like Raymond Roussel, for example, or Poe himself. And nevertheless, if the composition of objects of surrealism were arranged so as to produce what Walter Benjamin called a profane illumination, a luminosity, there is nothing less surrealist than Lizards, which produces a screech more than a spark, a disgust more than brilliance. It is a piece in which the components come into contact with one another less as doing an umbrella and a sewing machine on a dissection table (according to Lautréamont's image which Breton would quote as the exemplification of the surrealist image) as does a fingernail come into contact with the surface of a chalkboard.

Paul Valéry, in a 1932 text on Corot, says there are two great types of artists. On the one hand, there are the artists whose goal it is, to quote Valery, to make us "companions in his happy gaze on a beautiful day." Corot would exemplify precisely this group. And on the other hand, there are the Delacroixs, the Wagners, the Baudelaires, whose goal it is "to procure from their environments the most energetic action upon the senses," to be preoccupied with the "domination of the soul through the channel of the senses," anxious "to reach and as if to possess –in the diabolical sense of the term– that weak and hidden spot of the being that exposes it and governs it entirely by the deflection of its organic depths and guts."2 Tunga (like Nauman, like Richard Serra) clearly belong to this last category. In the large installations, the artist's desire to make an impact on the viewer and to control his or her reactions is clear. There is something of a hypnotist (magnetist as they used to say some time back) in the artist who composed those works. That desire is less visible, however, in his smaller works which are distributed in two identical rooms in the back part of the building –in the part of the building that faces the room where Ão spreads out– joined by a somewhat narrow hallway. One part of these pieces are separate versions, in general, realized earlier, as if they were sketches, of objects that make part of the composition of the installations: garrotes, rings, braids, combs, bundles of copper wire. Everything in these rooms resembles a human organ and at the same time a piece of jewelry. The combination of cruelty and luxury that appears to bear down on these two rooms imbues the works in the hallway that separates them with a strange light.

In fact, in the passageway between the two rooms one finds the most, let us say, lyrical works of the exhibit. They are a series of sculptures, made over the last ten years, since 1986, called Eixos Exoginos (Exogenous Axes). Anyone would surely remember those urns commonly used in psychology books on vision in whose outline one could pick out the profile of a human face. The same principle operates in these works. They are columns turned in such a manner that in its edges one can perceive, in each case, in the negative or in their absence, the profile of the full, naked body of a woman, different every time. There are five of these works in the exhibit and as a group they make one think of an elemental and frozen dance. They are related of course to the impressions of women made on paper or fabric produced in the fifties and sixties by Robert Rauschenberg and Yves Klein. But their appearance recalls more closely certain works by the sculptor which, in conversation Tunga, curiously seems to mention most frequently: Constantin Brancusi.

On the day of the inauguration of the show, this group of columns or portraits resonated with two other mobile groups of women: the participants in two performances. In one Xipofagas capilares (Capillary Xipophagi) from 1985) two girls were braided together by the hair as if they suffered from a relatively benign (for them) form of being Siamese twins, and simply walked back and forth. In the other performance, Sero te Amavi (Belatedly I Loved You) from 1992, three adolescent women wearing shirts, with thimbles, needles, and rings in their hands, assumed, frozen, a series of poses. In each one of the poses, each of the women, to all appearances indifferent to the others, would lean against the other two. (There was always something insufficiently erect in the figures, in the constructions they formed.) What idea regulated the composition of the poses of these three women? There is a topological figure called the Borromean knot which readers of the latest works of Lacan should be very familiar. A Borromean knot is composed of three interlocking rings such that should one of the three be broken the other two will also be freed. The same thing occurs with a braid of three strands: if any one of them is cut the other two will disperse. These three adolescents acted like a Borromean knot or a three-stranded braid: all it took was for one of them to fall for the other two to come down as well. Such that, at every moment throughout the course of the group's performance, each adolescent made contact with the others and stuck to the others to the extent possible.

What is the origin of these beings? The inspiration for this work (and the wording of its title) comes from a passage from the Confessions of Saint Augustine. The model for this group, this conglomeration, or this braid is the Holy Trinity of Christian doctrine. But what might this artist, so little Christian to all appearances, find especially attractive in that traditional figure? What is there for Tunga that is so particularly fascinating in the Holy Trinity?

The first time I saw this performance, in New York, only a few years ago, the three adolescent women were at the far end of a long gallery. In the front part of the gallery was an acrylic box packed with paper through which three snakes slithered. What is the relation, I wondered at the time, between a bunch of snakes and three immobile adolescents representing (the word is probably inadequate) the Holy Trinity? No being appears more in the work of Tunga than snakes, in particular, intertwined snakes. One of their appearances is now a decade old. In 1987, Tunga produced the sculptures and concepts for a film directed by Arthur Omar with the title Nervo de prata (Nerves of Silver). In one sequence of the film, the camera focuses with evident delight on several snakes that are intertwining. The camera captures the rubbing of skin against skin. It is as if the snakes were being moved by a desire to make contact with one another as completely as possible even at the price of losing their own distinction in a pile or mass of indistinguishable parts. However strange the idea might seem, it is possible that Tunga finds the figure of the Holy Trinity fascinating to the extent that it reminds him of the fascinating spectacle of intertwined snakes. Is not the Holy Trinity traditionally a composite of three beings who make ecstatic and total contact with one another? In which are combined the maximum absorption on the part of each one, abandoned to the pleasure of becoming experience and the maximum communication with the other parts, equally abandoned? The reading is violent and yet, I believe, fitting. An idea of the Holy Trinity, the trio of adolescents, the braided snakes. The braids of metal that appear briefly throughout this piece are perhaps momentary appearances of a fantasy of total pleasure in the perfect absorption of and pure communication with others.

Is it the insistence of this figure of pleasure which makes this piece so perturbing and fascinating? The remains of the performance can be found in Bard College in the room following the second of the rooms of small objects, opposite in the building to the Lizards room. Flexible rubber tubes extend from three corners of the room, the kind used for example in doctors' waiting rooms or offices to encircle the arm about to receive an injection. The three sections of tubing knot together borromeaneously in the middle of the room and on that knot are small (which is to say, normal-sized) versions of the objects magnified in Palindrome Incest: three thimbles (with a bit of red wine in each,) three thermometers, three needles that somehow manage to borromeanously knot together. Several shirt sleeves hang from the tubing. Three enormous candles which are lit during the performance lean against one another and are bound together with additional tubing. The three shirts of the three adolescents lie on the floor, spread out in a circle and touching each other, stained with wine and bearing a few tiny fragments of red glass and rings. A mute record of the performance, the three adolescents fallen down on the floor: it is the following moment that we now witness after the inauguration in this room. The arrangement is manifestly ceremonial but is also that of the crime scene preserved intact. Is it the tenuous drippings as if of highly diluted wax on the walls of the room that make its atmosphere –which is a rarity in Tunga's work– infinitely pallid? Everything in the room remains yet everything looks as if it were about to vanish. There is a text by Poe that seems to me to describe something of what takes place in this installation by Tunga. At the beginning of The Fall of the House of Usher the narrator of the story, standing in front of the old mansion mentioned in the title, is surprised by what he calls "a wild inconsistency between its still perfect adaptation of parts and the crumbling condition of the individual stones" and he compares the appearance of the whole, its "extensive decay to the specious totality of old woodwork which has rotted for long years in some neglected vault, with no disturbance from the breath of the external air."3 There is something at once of confinement and of desperate fragility in these fragments and something deceiving in its apparent wholeness. It is a sight of final moments.

That fragility of the vestiges of Belatedly I Loved You does nothing to prepare the viewer for the installation in the final room, altogether occupied (over-occupied, one might say) by the massive presence of Cadentes lacteos (The Milky Fallings) from 1994. The last two rooms constitute in the show a sort of brief suite to the fall. What falls in the final work of the show are several enormous metallic bells. The gigantic scale of this work is similar to that of Palindrome Incest, which is located in its corresponding room. There are five bells in the room, three hung, and two tumbled on the floor. Several objects resembling vessels are stuck to their surfaces which are additionally covered with a whitish substance that reminds one of semen, and which trickles down toward the floor. In a particularly splendid passage in Residence on Earth by Pablo Neruda, the poet communicates the following vision: "And although I close my eyes and fully cover my heart, I see deaf water falling in enormous deaf drops. It is like a hurricane of gelatin, like a waterfall of sperm and jellyfish".4 Putting aside Neruda's expressionist tone which Tunga doesn't share. The Milky Fallings could be presented as a rather idiosyncratic illustration of the poet's lines. The artist would probably appreciate the combination, the contrast between the literally hurricane whipped violence of vision and the inconsistency of the materials that appear within it: gelatin, sperm, or jellyfish.

But Tunga would also find it immediately attractive that, under the title of Sexual Water (the title of the poem from which the quoted lines were taken), Neruda evokes a catastrophic state of the body. A recurring figure in the recent performances of the artist (performances that have not been included in the Bard exhibit) is a man carrying a suitcase. The suitcase suddenly opens and out of it falls a pile of selected limbs mixed with cubes of gelatin. Do these limbs belong to the disappeared adolescents in Belatedly I Loved You? We are not in a position to answer that question. But it is interesting that the Bard show would close with an image that indicates, beyond itself, some obscure disaster. It is not impossible that, at this stage in the viewing, he who has come through the exhibit might perceive that that voice that in Ão keeps falling into a stunning babbling, or the scene of a sewing room invaded by metals, or the Siamese lizards and tiny brains mixed with hair that extends itself without limit, or some bells tossed like dice and impregnated with a milky liquid, or the somnambulist collapse of a knot of adolescents, that all those figures refer to a threatened existence. (In a video which is shown at Bard in a side room, Tunga is constructing several pieces. His gestures are strange it is as if, at the same time he is making his constructions, Tunga wishes to keep them at a distance to avoid who knows what danger.) A specific affection is capable, I believe, of producing this show: a pleasure, a euphoria, in total contact, entirely intertwined, in every one of its moments, with an uneasiness. The specific nature of this affection is, for this writer, new.

NOTES

1. A comprehensive list of these activities can now be found in a book by the artist published this year: Barroco de lirios, (São Paulo: Kosac & Naify, 1997). The bibliography on Tunga is still limited. Fine texts written by Guy Brett, Suely Rolnik, and Carlos Basualdo, will be published in the exhibition catalog.

2. Paul Valéry, Pieces sur I'art (Paris: N.R.F., 1936) 137-138.

3. Edgar Allan Poe, trans. D. Rolfe and J. Gomez de la Sema (Madrid: Ccitedra, 1991) 169.

4. Pablo Neruda, Residencia en la tierra (Madrid: Ccitedra, 1986).

REINALDO LADDAGA

Author and Ph.D. Candidate at New York University. He teaches at several universities in Argentina and the U.S. He has published extensively on aesthetics, art, and literature issues.

Comentarios