Japón abre los ojos a las fotógrafas y a la mirada femenina.

- OCA | News

- 15 abr

- 7 Min. de lectura

Hasta hace poco, se les había negado el reconocimiento e incluso el crédito por su trabajo, pero las fotógrafas japonesas están desafiando y subvirtiendo las suposiciones tradicionales sobre el cuerpo femenino.

OCA|News Japón abre los ojos / Lunes 14 de abril, 2025 / Internacional / Español / English

Art Newspapers / Lisa Movius

La "década perdida" de Japón fue una época de descubrimiento para las fotógrafas del país. Más allá de la desvinculación del arte comercial que puede conllevar las crisis económicas, la Ley de Igualdad de oportunidades en el empleo de 1986 estaba transformando la sociedad a mediados de la década de 1990. Curadoras como Kasahara Michiko (curadora jefe del Museo de Arte Fotográfico de Tokio) y la revista Main Foto, dirigida entre 1996 y 2000 por las fotógrafas Ishiuchi Miyako y Narahashi Asako, impulsaron nuevos movimientos feministas, desde la denostada "foto femenina", precursora de las redes sociales, hasta las tajantes refutaciones del "arte del cabello" (o "hair art"), una mirada pornográfica masculina.

La exclusión y la invisibilidad han sido históricamente la norma. Durante décadas, la fotógrafa japonesa más antigua conocida, Shima Ryū, no fue reconocida por los álbumes de la década de 1860 que produjo con su esposo. Takeuchi Mariko, crítica de fotografía, curadora y profesora de la Universidad de las Artes de Kioto, en su ensayo "Mujeres disidentes" para el presente estudio, recuerda que en 1995 un famoso fotógrafo le dijo que casarse con alguien rico era la única manera de convertirse en fotógrafa.

Mientras tanto, Fotógrafas Japonesas, una prestigiosa serie de fotolibros de la década de 1990, llegó a los 40 volúmenes sin incluir a ninguna mujer. Incluso hoy, las fotógrafas pioneras son menos conocidas que sus colegas masculinos: el Foro Económico Mundial en 2021 clasificó a Japón en el puesto 120 de 156 países en igualdad de género.

Visibilidad

I’m So Happy You Are Here (el título proviene de un poema de Kawauchi Rinko) busca remediar esta situación. El ensayo de Takeuchi es uno de los tres que establecen los contextos y la historia de las fotógrafas japonesas, que abarcan desde la Segunda Guerra Mundial y la ocupación estadounidense hasta el terremoto y el desastre nuclear de Tohoku de 2011. Pauline Vermare, curadora de fotografía del Museo de Brooklyn, coedita con Lesley A. Martin, directora ejecutiva de Printed Matter Inc.

Los portafolios de 25 fotógrafas van seguidos de una bibliografía exhaustiva de fotolibros (contribución de Marc Feustel y Russet Lederman). Una recopilación de textos históricos, muchos de ellos publicados por primera vez en inglés, enriquece este impresionante volumen, que abarca a un total de 60 fotógrafos.

En el primer ensayo, Vermare rastrea la fotografía japonesa femenina desde Shima, pasando por la moda de la década de 1930, hasta la vibrante, aunque poco reconocida, fotografía femenina de las décadas de 1950 a 1990. Hombres como Araki Nobuyoshi y Sugimoto Hiroshi alcanzaron la fama en la década de 1970: la exposición "Nueva Fotografía Japonesa" del Museo de Arte Moderno de Nueva York de 1974 contó con 15 hombres, mientras que la exposición "Japón: Un Autorretrato" del Centro Internacional de Fotografía de Nueva York de 1979 contó con al menos una mujer, Ishiuchi, junto a 18 fotógrafos.

Ishiuchi, fotógrafa documental nacida en 1947, fue la organizadora de la influyente exposición Hyakka ryōran (Cien flores florecen) de 1976 en la Galería Shimizu de Yokohama, y una de las diez mujeres que participaron. Posteriormente, en 1987, se presentó Fotógrafas Japonesas: De los años 50 a los 80 en las Galerías de Arte de la Universidad de Lehigh en Bethlehem, Pensilvania, impulsada por Ricardo Viera, artista, profesor y curador cubano, después de que un grupo de hombres japoneses boicoteara lo que inicialmente fue una presentación mixta. Sin embargo, pasaron once años antes de que la galería Visual Studies Workshop de Rochester, Nueva York, presentara Una Historia Incompleta: Fotógrafas de Japón 1864-1997.

El primer fotolibro publicado en Japón por una mujer fue Dangerous Poison Flowers de Tokiwa Toyoko (1930-2019). Publicada en 1957, su documentación sobre trabajadoras sexuales al servicio de soldados estadounidenses en Yokohama se realizó justo antes de la promulgación de la ley anti prostitución de 1958. Miembro del colectivo fotográfico Vivo y del Club de Cámara Shirayuri, formado exclusivamente por mujeres, Tokiwa participó en la influyente exposición de 1957 "Ojos de Diez" en la Galería Konishiroko de Tokio. Posteriormente, se convertiría en una fotoperiodista viajera por el mundo.

Cortesía de Third Gallery Aya (Osaka) y Aperture.

El sexo comercial en los alrededores de las bases estadounidenses fue un tema para varias generaciones de fotógrafos, incluyendo a Ishiuchi, quien politiza su historia personal con su fotolibro "Apartamento" (1978), que documenta la desaparición de viviendas compartidas en edificios antiguos y deteriorados, muchos de ellos antiguos burdeles. Le siguieron Endless Night (1981), centrada en un burdel, y Mother’s (2002), con objetos íntimos que dejó tras la muerte de sus padres.

Batallas discográficas

Matsumoto Michiko (nacida en 1950), cuya foto de 1978

Japan is opening its eyes to women photographers—and to the female gaze

Denied recognition and even credit for their work until recent times, Japan’s women photographers are challenging and subverting traditional assumptions about the female body.

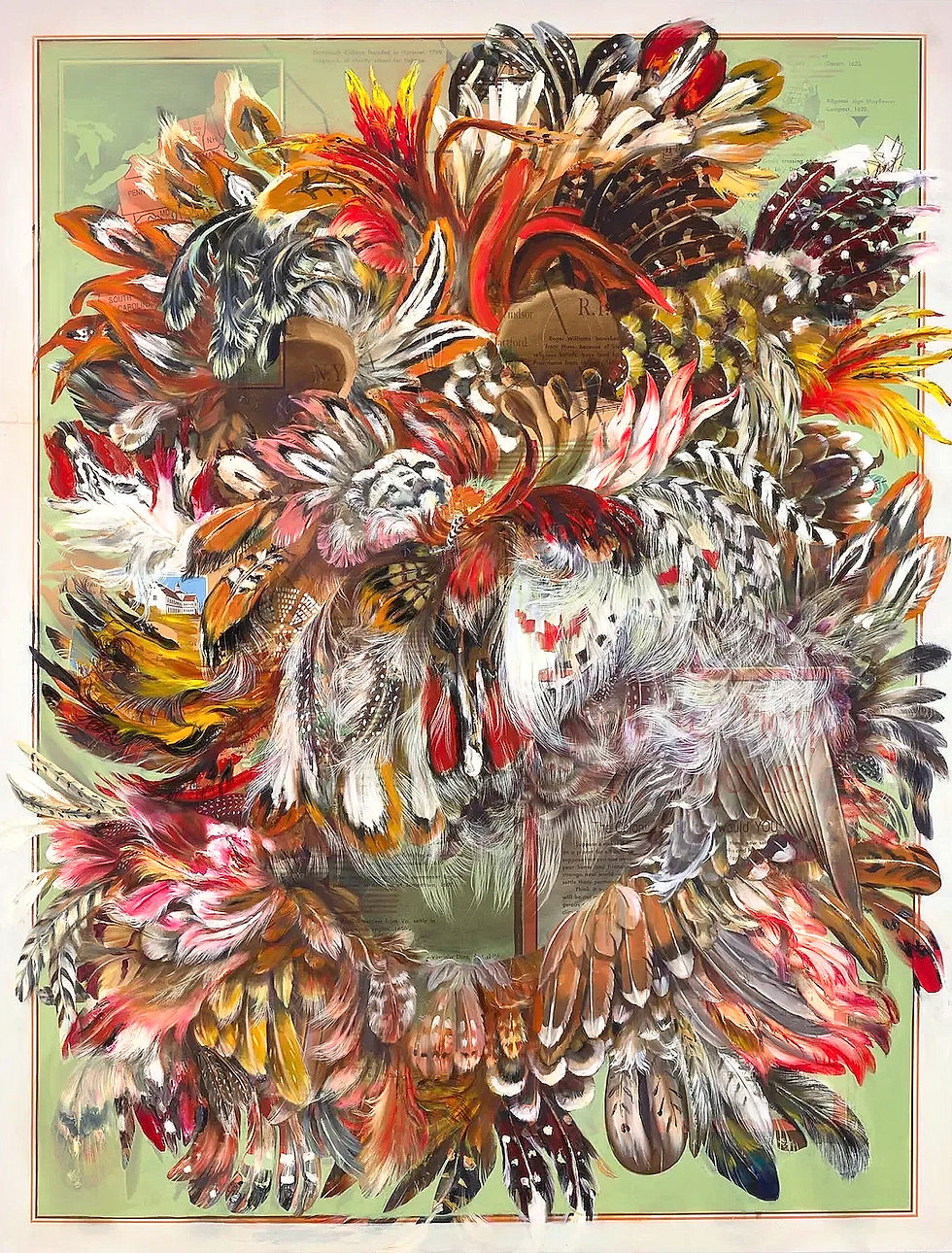

Female vision: Kawauchi Rinko’s Untitled from her the eyes, the ears series

Courtesy the artist and Aperture

Female vision: Kawauchi Rinko’s Untitled from her the eyes, the ears series

Japan is opening its eyes to women photographers—and to the female gaze

Japan’s “lost decade” was a time of discovery for the nation’s female photographers. Beyond the decoupling from commercial art that can come with economic busts, a 1986 Equal Employment Opportunity Law was reshaping society by the mid-1990s. Curators such as Kasahara Michiko (the chief curator at the Tokyo Photographic Art Museum) and Main Foto Magazine, run between 1996 and 2000 by the female photographers Ishiuchi Miyako and Narahashi Asako, fomented new female-centric movements, from the derided social media precursor “girly photo” to sharp rebuttals of the porny male-gaze “hair art”.

Exclusion and invisibility have been historically the norm. For decades, Japan’s earliest known female photographer, Shima Ryū, was uncredited for the 1860s albums she produced with her husband. Takeuchi Mariko, the photography critic, curator and professor at Kyoto University of the Arts, in her essay “Dissident Women” for the present study, recalls being told in 1995 by a famous male photographer that marrying into wealth was the only way she could become a photographer.

Meanwhile, Japanese Photographers, a prestigious 1990s photobook series, ran to 40 volumes without including a single woman. Even today, groundbreaking female photographers are less recognised than their male peers: the World Economic Forum in 2021 ranked Japan 120 out of 156 countries on gender equality.

Made visible

I’m So Happy You Are Here (the title comes from a Kawauchi Rinko poem) seeks to remedy this. Takeuchi’s essay is one of three establishing the contexts and history of Japanese women photographers, which thread through the Second World War and American occupation to the 2011 Tohoku earthquake and nuclear disaster. Pauline Vermare, the curator of photography at Brooklyn Museum, co-edits with Lesley A. Martin, the executive director of Printed Matter Inc.

Portfolios of 25 photographers are followed by an in-depth bibliography of photobooks (contributed by Marc Feustel and Russet Lederman). A compilation of historical texts, many appearing in English for the first time, fleshes out this impressive volume, which covers about 60 photographers in total.

In the first essay, Vermare traces female Japanese photography from Shima through 1930s fashion to the vibrant if unrecognised female photography of the 1950s to the 1990s. Men including Araki Nobuyoshi and Sugimoto Hiroshi found fame in the 1970s: the 1974 New York Museum of Modern Art show New Japanese Photography featured 15 men, while New York’s International Center of Photography’s 1979 exhibition Japan: A Self-Portrait at least had one woman, Ishiuchi, alongside 18 male photographers.

Breakthrough

Ishiuchi, a documentary photographer born in 1947, was the organiser of the seminal 1976 show Hyakka ryōran (one hundred flowers bloom) at Shimizu Gallery, Yokohama, and one of the ten women included in it. Then in 1987 came Japanese Women Photographers: From the 50s to the 80s at Lehigh University Art Galleries in Bethlehem, Pennsylvania, instigated by Ricardo Viera, the Cuban artist, professor and curator, after a group of Japanese men boycotted what had started out as a mixed-gender presentation. Another 11 years passed, though, before An Incomplete History: Women Photographers from Japan 1864-1997 was staged by the Visual Studies Workshop gallery in Rochester, New York.

Japan’s first published photobook by a woman was Dangerous Poison Flowers by Tokiwa Toyoko (1930-2019). Appearing in 1957, its documentation of sex workers serving American soldiers in Yokohama was shot just ahead of a 1958 anti-prostitution law. A member of the Vivo photographic collective and the all-women Shirayuri Camera Club, Tokiwa was included in the influential 1957 show Eyes of Ten at Konishiroko Gallery, Tokyo. She would go on to become a globetrotting photojournalist.

Mother’s #39 (2002) by Ishiuchi Miyako, who organised and featured in Japan’s first all-women photography exhibition in 1976

Courtesy Third Gallery Aya (Osaka) and Aperture

Commercial sex around US bases provided a subject for several generations of photographers, including Ishiuchi, who made the personal political with her photobook Apartment (1978), documenting vanishing shared dwellings in dilapidated old buildings, many of them former brothels. It was followed by the brothel-focused Endless Night (1981), and then Mother’s (2002), with intimate items left behind after her parent’s death.

Label battles

Matsumoto Michiko (born 1950)—whose 1978 photobook Women Come Alive documented women’s movements in Japan and US—explicitly identifies as feminist, and was part of a counterculture that included the writer Yoshimoto Banana and Fluxus members Kubota Shigeko and Ono Yoko. Other photographers, such as Ishiuchi and Ishikawa Mao, were involved in Japan’s 1960s ūmanribu gender liberation movement, but eschewed the feminist label as much as that of joryū (feminine).

Ambivalence over such designations has persisted, even among those presenting female sexual nonconformity in response to Araki-style “hair nudes”, derived from the term for the outlawed “pubic hair nudes”. In 1994 Nomura Sakiko published Naked Room: male nudes that subverted the sexual gaze despite rejecting association with feminism. After showing in Japan since 1993, Nagashima Yurie’s often nude family and self-portraits were critiqued when later presented in the US as exploiting her own sexuality and pandering to Orientalist clichés of the sexually submissive geisha. It surprised her, Vermare writes, since that stereotype only exists abroad; in Japan, geisha are entertainers, not sex workers.

The present brings us, for example, the painterly Rinko, and the multifaceted Katayama Mari. Born in 1987 with tibial hemimelia, causing bone underdevelopment, Katayama had both her legs amputated at the age of nine. Her work challenges ableist, normative presumptions by staging her unusual body alongside limbless mannequin torsos or splayed with myriad arms like a beached sea creature. Her nuanced confidence in the “self as subject” draws from a rich tradition of the women who came before.

• I’m So Happy You Are Here: Japanese Women Photographers from the 1950s to Now, edited by Pauline Vermare and Lesley A. Martin, published by Aperture, 440pp, 518 colour illustrations, $75/£60 (hb), published 17 September 2024

Comentarios